1.7.2 – Inpainting

Using the techniques above, we can also modify our

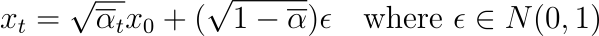

iterative_denoise_cfg function to edit certain sections of an image. To do so, we first define a mask the same size as the image that is 1 at the pixels where we want to edit, and 0 otherwise. For each loop of the denoising process, we replace

xt with

mxt + (1 -

m)forward(

x0, t), where

m is the mask and

x0 is the original image.

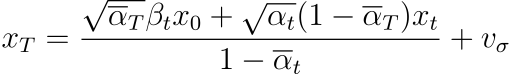

Once

image is replaced by

masked_image, we replace all further occurrences of

image except for the last instance, as the image at each step still needs to be updated. Finally, we let our starting noise be purely random and start with a timestamp index of 0, so that the patch we want to change can be sufficiently denoised. Below are the results on the Campanile image:

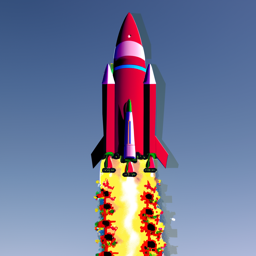

Campanile Inpainting

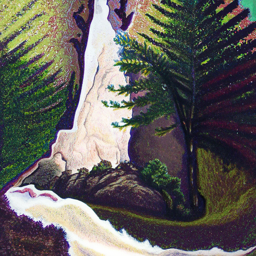

Below are 2 other examples of inpainting similar images: